The late eighteenth century witnessed a dramatic shift in American life. The increasing impact of industrialization was evidenced by the mass shift of people from rural communities to urban areas. The Industrial Revolution reshaped the nation, especially in the North.[1] Institutional religion needed to address the rapid industrialization, urbanization, and immigration of the period.

Two distinct religious movements arose to respond to the issues of the cities and their effect on the nation. The Social Gospel offered a critique of the consumeristic ethos of the industrialized city while the Prosperity Gospel embraced this ethos and attempted to sanctify it by covering it with a Christian veneer.[2] While these movements were separated in goals and methods, they also possess some similarities that the casual observer may not recognize. Are these two responses completely at odds with one another or can the two mix? What prompted these movements?

The Social Gospel and the Prosperity Gospel seek to provide answers for individuals lost in the crowds of people found in the changing American culture of the late eighteenth and early twentieth centuries. This essay seeks to demonstrate the similarities and differences between these movements. To do this, the first section will examine the historical backgrounds and influences of these movements. Once an understanding of the influences of the movements is understood, the next section will note each movement’s main teachings. The subsequent section will examine the similarities and differences between the movements. The final section will see how the movements have fared in the period following World War I.

Backgrounds

The Industrial Revolution radically changed American society over thirty years. The population shifted from primarily rural farms to urban manufacturing. Industrialization, modernization, and urbanization raised new social questions that the governments and the churches were struggling to answer.[1] An awareness took the nation by storm as a series of exposés told of the poverty, suffering, and ignorance of the slums. The cities were breeding poverty, misery, vice, and crime.[2] The increased immigration of the period led to additional social questions. Most of these immigrants sought employment in the cities.

Vigorous capitalism had been laid in the foundations of modern America by the industrial order of the day. With it came corruption in the local, state, and national governments. This corruption was widespread and, in many places, unashamed.[3]

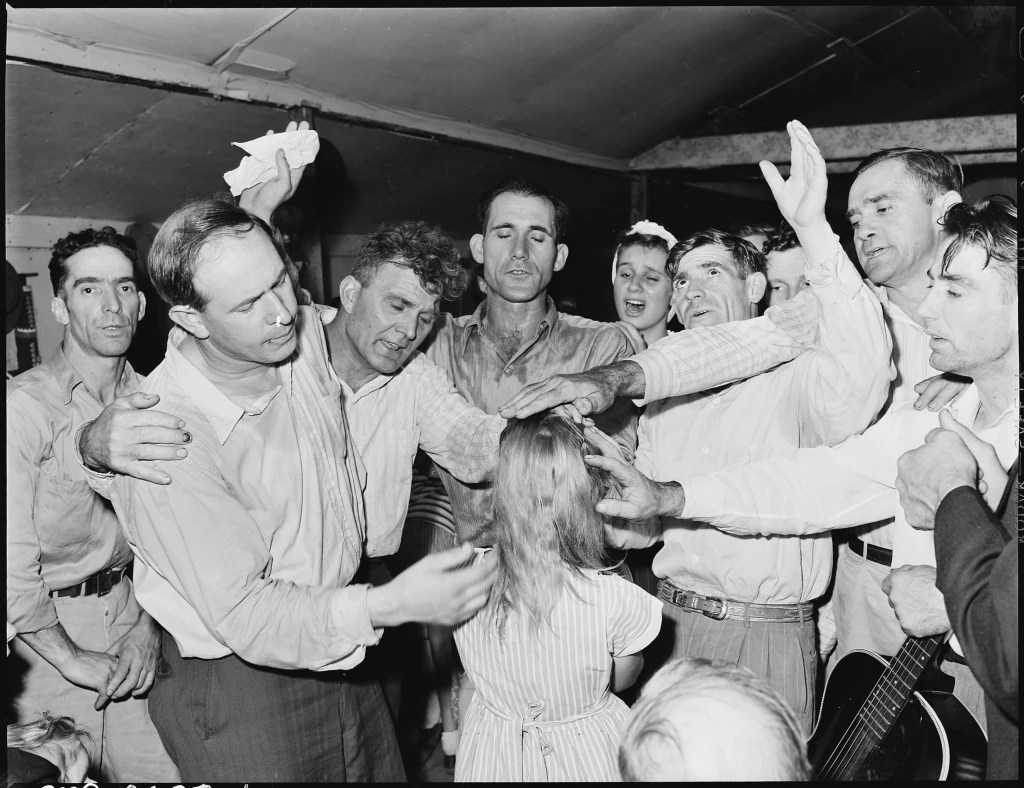

Alongside the rise of industrialization and capitalism, the Pentecostal movement arose.[4] The first wave of Pentecostalism arrived in the early nineteen-hundreds with a focus on the baptism of the Spirit as evidenced by speaking in tongues.[5] Both movements have connections with the Pentecostal movement. The Pentecostal movement itself sprung from the revivalism of the eighteenth century’s Second Great Awakening with its focus on free worship and the experiences of the Spirit.

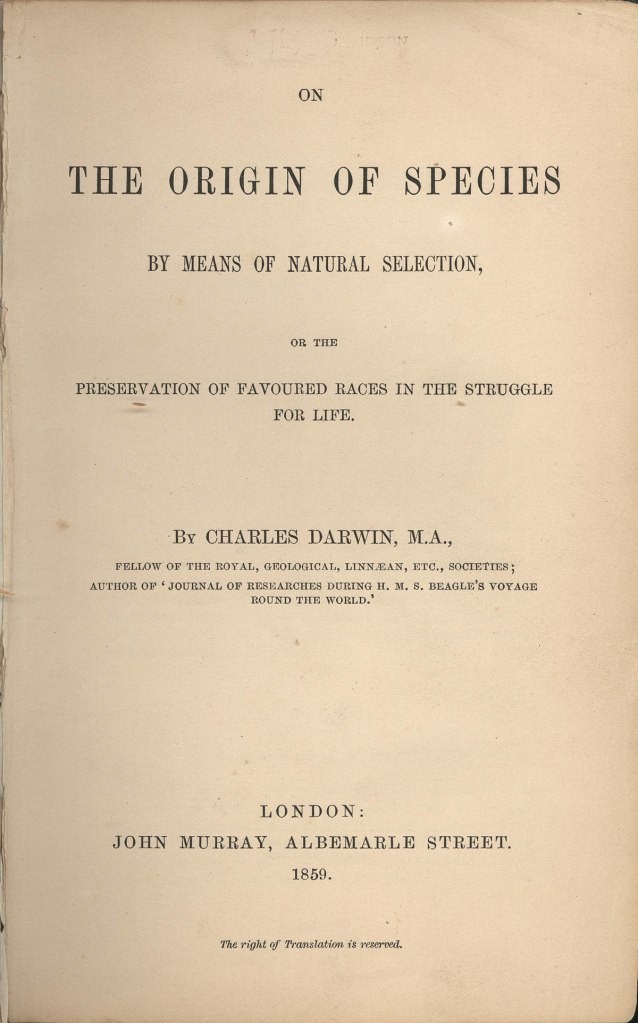

Modern scientific thought was also changing with the increasing acceptance of Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection. The last decade of the nineteenth century witnessed the acceptance of the Darwinian theory of evolution by progressive American theologians.[6] The various issues combined to create a period of economic and social instability that the church needed to address.

[1]Christina Littlefield and Falon Opsahl, “Promulgating the Kingdom: Social Gospel Muckraker Josiah Strong” American Journalism Vol 34, Issue 3 (Summer 2017), 297.

[2]Robert T. Tandy, The Social Gospel in America 1870-1920 (New York: Oxford Press, 1966), 9

[3]Charles Howard Hopkins, The Rise of the Social Gospel in American Protestantism: 1865-1915 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1940), 11.

[4]Katherine Attanasi and Amos Yong, Pentecostalism and Prosperity: The Socio-Economics of the Global Charistmatic Movement (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2012), 132-133

[5]Jerry Vines, Spirit Works: Charismatic Practices and the Bible (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1999), 12.

[6]Hopkins, The Rise of the Social Gospel, 123

Ideological Roots of the Social Gospel

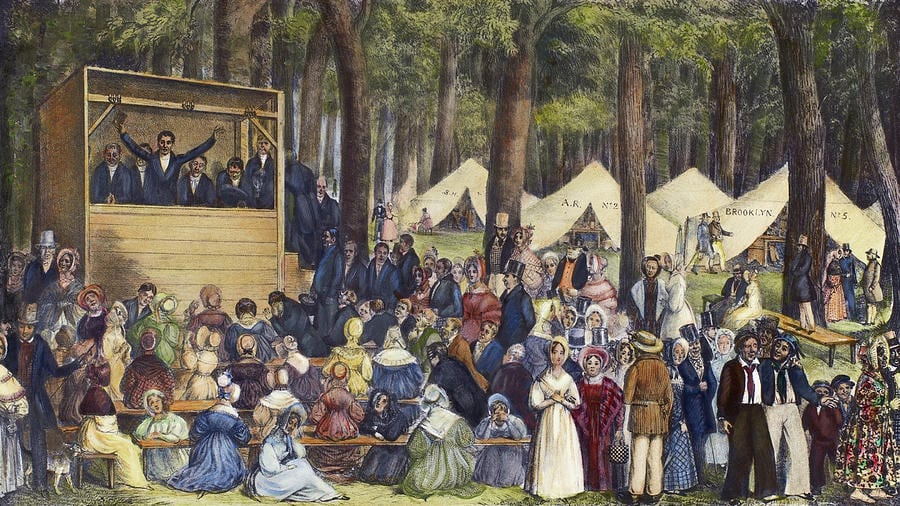

The basic concept of the Social Gospel grew from the revivalism of the previous two centuries. Both were concerned with attempts to Christianize the nation.[1] Awakenings in America had always had social, political, and economic results.[2] Decades of non-stop revivals had developed alongside and intermingled with reform movements to address the social issues of the times.[3] However, the denominate evangelical religions of those Awakenings had long emphasized individualistic salvation. The Social Gospel sought to bring salvation socially.[4] This will be discussed in greater detail in the next section.

The main thinkers of the Social Gospel were generally adherents to liberal theology.[5] Social Gospel leader Washington Gladden was a spokesman for liberal theology.[6] America’s best-known Social Gospel advocate and systematic theologian Walter Rauschenbusch[7] was also a proponent of liberal theology. Charles Hopkins even contended that the ideological foundation of the Social Gospel was to be found in Unitarianism.[8]

Gary Dorrien claimed that the Social Gospel was essentially a North American version of the movement for Christian Socialism that arose in Europe in the late nineteenth century.[9] According to this theory, English Christian Socialism came to the United States primarily through the Episcopal church.[10] New Theology teaching was a stimulus to the socialization of American Protestantism.[11]

[1]Ronald C. White, Jr and C. Howard Hopkins, The Social Gospel: Religion and Reform in Changing America (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1976), xiv.

[2]Ibid, 5.

[3]Littlefield and Opsahl, “Promulgating the Kingdom,” 292.

[4]White and Hopkins, The Social Gospel, 3.

[5]Tandy, The Social Gospel in America, 6.

[6]Ibid, 23.

[7]Ibid, 253.

[8]Hopkins, The Rise of the Social Gospel, 4.

[9]Gary Dorrien, “Society as the Subject of Redemption: The Relevance of the Social Gospel” Tikkun (Duke University Press) 24, no. 6 (November 2009), 43.

[10]White and Hopkins, The Social Gospel, 26.

[11]Ibid, 31.

Ideological Roots of the Prosperity Gospel

Three main developments influenced the Prosperity Gospel. Perhaps the most influential comes from a seemingly unlikely source, the cultic teachings of New Thought. The bulk of Prosperity Gospel teaching can be traced to New Thought metaphysics.[1] New Thought was an ideology that gained popularity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It drew from the Gospels, Hinduism, philosophical idealism, transcendentalism, popular science evolution, and the optimistic spirit of progress. In other words, it was a combination of pagan and Christian philosophies.[2] Emanuel Swedenborg of Sweden, a theologian, philosopher, and mystic, wrote several works which espoused similar thoughts to New Thought ideology. These were widely distributed and read in America.[3] Phineas Quimby believed sickness to be simply a disturbance in the mind. He believed that the way Jesus cured people was by convincing them to change their minds about their illnesses.[4] The connection between prosperity teaching and cultic teaching has been clearly shown by several writers.[5] The Prosperity Gospel simply encases New Thought teachings in a Christian veneer.[6]

The Prosperity Gospel is closely connected with Pentecostalism and the later Charismatic movement. Many Prosperity Gospel churches are affiliated with Pentecostalism’s free worship style and emotionalism. Several of the movement’s key leaders come from Pentecostal backgrounds. Numerous Prosperity preachers draw upon the Pentecostal tradition of personal visions of Jesus or point to out-of-body experiences.[7] Despite this close connection, some of the most scholarly rebuttals of the Prosperity Gospel have come from members of the Pentecostal community.[8] Most consider it a travesty that Prosperity preachers have been able to disguise themselves as Charismatic or Pentecostal.[9] These critics claim that the Prosperity Gospel is not Charismatic, but cultic.[10]

The Prosperity Gospel was birthed in capitalism in the development of the United States, soon to become the world’s leading free-market economy.[11] As such, prosperity theology developed amid the progressive globalization of modern capitalism.[12] The movement harnessed capitalism for its purposes, as will be seen in more detail in the next section.[13] It is because of this embrace and the effect of globalized capitalism that the Prosperity Gospel resonates with so many people.[14]

[1]Hank Hanegraaff, Christianity in Crisis (Eugene: Harvest House Publishers, 1993), 29

[2]David W. Jones and Russell S. Woodbridge, Health, Wealth, and Happiness: Has the Prosperity Gospel Overshadowed the Gospel of Christ? (Grand Rapids: Kregel Publications, 2011), 27-28.

[3]Ibid, 28-29.

[4]Ibid, 30-31.

[5] Vines, SpiritWorks, 166.

[6]Jones and Woodbridge, Health, Wealth, and Happiness, 34.

[7]Hanegraaff, Christianity in Crisis, 76.

[8]Ibid, 49.

[9]Ibid, 48.

[10]Ibid, 47.

[11]Attanasi and Yong, Pentecostalism and Prosperity, 215.

[12]Ibid, 131.

[13]Mary V. Wrenn, “Consecrating Capitalism: The United States Prosperity Gospel and Neoliberalism” Journal of Economic Issues (Taylor & Francis Ltd) 53, no. 2 (June 2019), 429.

[14]Attanasi and Yong, Pentecostalism and Prosperity, 131.

Join me next week as I continue to examine the Social Gospel and the Prosperity Gospel’s major teachings.

Leave a comment