Last week I began a series of posts comparing the Social Gospel and the Prosperity Gospel. I began by examining the background that led to the rise of these movements. This week I continue this study by examining the major teachings of each movement.

Both movements had to develop their major teachings considering their contemporary situations. They sought to answer the questions on the minds of most people living in the cities who were feeling the weight of capitalism, urbanization, immigration, scientific naturalism, and social upheaval. Therefore, an examination of each movement’s major teachings is required.

Primary Doctrines of the Social Gospel

The Social Gospel was not a unified movement. There were disagreements within the movement which contradicted or disagreed with each other. There were two extremes within the movement. Conservative groups wanted to focus on the individual while the most liberal wanted to impose strict socialism. The position between these groups is the most applicable to apply broadly to the movement.[1] Walter Rauschenbusch was the premier theologian for the Social Gospel. In the introduction to his theological work, he wrote that the Social Gospel needed a theology to make it effective, but the theology needed the Social Gospel to vitalize it.[2] The main doctrines of the movement are detailed below.

Focus on Institutional Sin

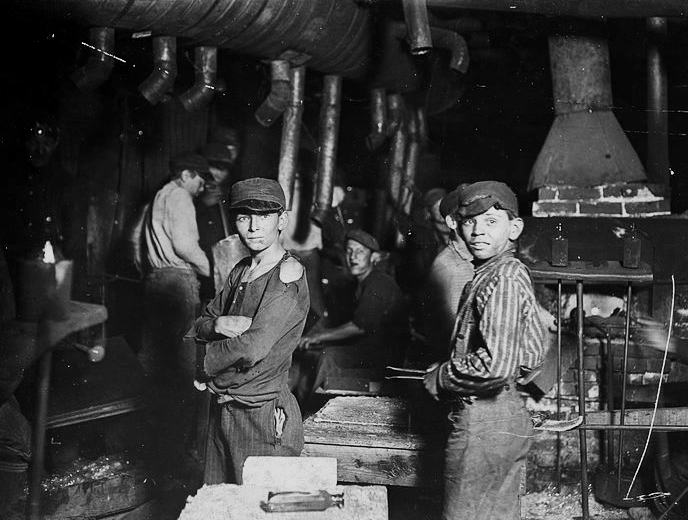

The Social Gospel is based on the idea of social salvation.[1] Nowhere was the need for social salvation witnessed more than in the new sprawling cities with their inescapable social problems.[2] In the cities, the dangers of Romanism, socialism, wealth, intemperance, and immigration were enhanced and focused.[3] The problems of the city were seen as the advanced problems of the nation and the world.[4] The labor strife of the late nineteenth century thrust the social problems before the nation in a dramatic way.[5] There was a great need for social reform in the cities, but nothing was being done about it.

The church had long been a charity leader, but not in social reconstruction.[6] The slow progress of Christianity was blamed on traditional churches’ preoccupation with creeds and doctrine rather than true charity.[7] Despite the church’s noble achievements, the ethic of orthodoxy had become a sterile union of formalism and individualism.[8]

While traditional Protestant religion taught that the gospel was primarily to transform the individual, the Social Gospel understood that individuals are closely connected with other individuals. They were confident that the gospel is not only sufficient for the individual, but for transforming society as well.[9] A gospel of individual salvation was on a half-gospel, for the gospel had social dimensions as well.[10] The Christian is to allow God to work within him to bring a better social order.[11] The Social Gospel seeks to bring men to repentance for their collective sin, not just their individual sin.[12] It called for an expansion in the scope of salvation.[13]

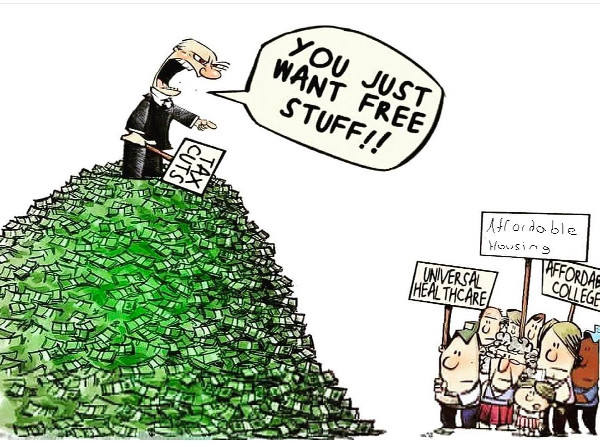

The Social Gospel was therefore also a critic of capitalism. It viewed capitalism as the great evil which did not consider the human element in the cities’ life.[14] Explicit criticism of capitalism was a common refrain.[15] No matter how vast the capitalization, all capital is administered by human beings. Human beings must treat other human beings as persons.[16] Rauschenbusch argued that the rise of corporate capitalism marked a crisis for American civilization.[17] He asserted that capitalism provides for speed labor and production of wealth, but leaves a trail of human misery, discontentment, bitterness, and demoralization.[18] Due to this belief, he argued that the only true Christian government must be a Socialist government.

Economist Richard T. Ely was an early leader of the movement. He expressed the Social Gospel’s high view of the role of government. He claimed that the state is a divine institution through which God works more than any other institution.[19] The state is the most inclusive of the divine institutions as it covers all individuals of the area, regardless of the individual’s religion.[20] It was for this reason that the United States must be recognized as a Christian nation.[21] As Mathews writes, “Social needs aroused by Christianity cannot be met by the ideals of any non-Christian religion.”[22] This high view of the State is intricately tied to the movement’s concept of the kingdom of God.

[1]Dorrien, “Society as the Subject of Redemption,” 43.

[2]Tandy, The Social Gospel in America, 4.

[3]White and Hopkins, The Social Gospel, 57.

[4]Ibid, 61.

[5] Tandy, The Social Gospel in America, 9.

[6]Shailer Mathews, The Individual and the Gospel (New York: Missionary Education Movement of the United States and Canda, 1914), 3.

[7]Hopkins, The Rise of the Social Gospel, 6.

[8]Ibid, 18.

[9]Mathews, The Individual and the Gospel, 1-8.

[10]Christopher H. Evans, The Social Gospel Today (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001), xiii.

[11]Shailer Mathews, The Social Gospel (Philadelphia: The Griffith & Rowland Press, 1910), 29.

[12]Rauschenbusch, A Theology for the Social Gospel, 5.

[13]Ibid, 11.

[14]White and Hopkins, The Social Gospel, 53.

[15] Hopkins, The Rise of the Social Gospel, 27.

[16]Shailer, The Social Gospel, 108.

[17]Dorrien, “Society as the Subject of Redemption,” 44.

[18]Rauschenbusch, A Theology for the Social Gospel, 113.

[19]Tandy, The Social Gospel in America, 219-244.

[20]Ibid, 182.

[21]Ibid, 249.

[22]Mathews, The Individual and the Gospel, 2.

The Kingdom of God

Rauschenbusch’s central theological concept was the Kingdom of God.[1] This idea claims that the kingdom of God is at hand. Jesus brought the kingdom of God, but it was obscured by the individualistic gospel.[2] The kingdom of God is not something that awaits in the eschaton but is here and now. Therefore, the church must fully work to improve society to make that kingdom known on the earth.

The goal is to reduce evil in the world. This evil is evident in three stages: sin against the individual’s higher self, sin against the good of men, and sin against the universal good. Sin is equated with selfishness. It is against society rather than a private transaction between the sinner and God. The sinful mind is the unsocial and antisocial mind. Inactiveness in improving the conditions of man is active selfishness. This sinfulness is not individualistic but transmitted as social customs as one generation corrupts the next. Salvation is therefore turning away from selfishness to a life focused on God and one’s fellow man.[3] Therefore, “The individual is saved, if at all, by membership in a community which has salvation.”[4] The Social Gospel is primarily concerned with how the life of Christ affects human society.[5]

This view of the kingdom of God and a high view of the State led many in the movement to embrace Socialism as the only proper form of government. Rauschenbusch’s book was a manifesto for democratic socialism. The purpose of prophetic biblical religion in the transformation of society was to lead to a divine commonwealth of freedom, equality, democracy, and community.[6] The way he describes it, the end goal for society is Socialism.[7]

The universal dream of Social Gospel proponents was that the reformation of American society would lead to international reform. The United States would be the chosen instrument of God to move the world toward righteousness.[8] According to Mathews, “Jesus must and can save the world by transforming it into the kingdom of God.” This is the heart of the social gospel.[9] As American society was to transform into a more perfect kingdom of God, the nation was expected to export this kingdom through imperialism.

[1]Hopkins, The Rise of the Social Gospel, 221.

[2]Rauschenbusch, A Theology for the Social Gospel, 21.

[3]Ibid, 43-55.

[4]Ibid, 126.

[5]Ibid, 147-148.

[6]Dorrien, “Society as the Subject of Redemption,” 44.

[7]Rauschenbusch, A Theology for the Social Gospel, 224.

[8]White and Hopkins, The Social Gospel, 114.

[9]Mathews, The Individual and the Gospel, 68.

Liberal Theology

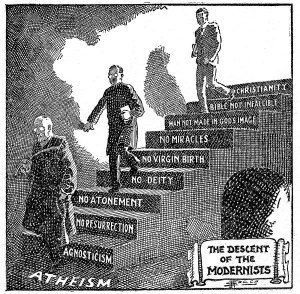

Early leaders in the movement embraced liberal theological teachings. Washington Gladden believed that the Bible was not an infallible book and to claim it was is to be guilty of grave disloyalty to the kingdom of truth. In his view, the Bible is primarily concerned with ethics and records how men have failed to live ethically.[1] Rauschenbusch espoused liberal theology in his work, elevating Friedrich Schleiermacher and rejecting concepts like the Fall and the reality of Satan.[2]

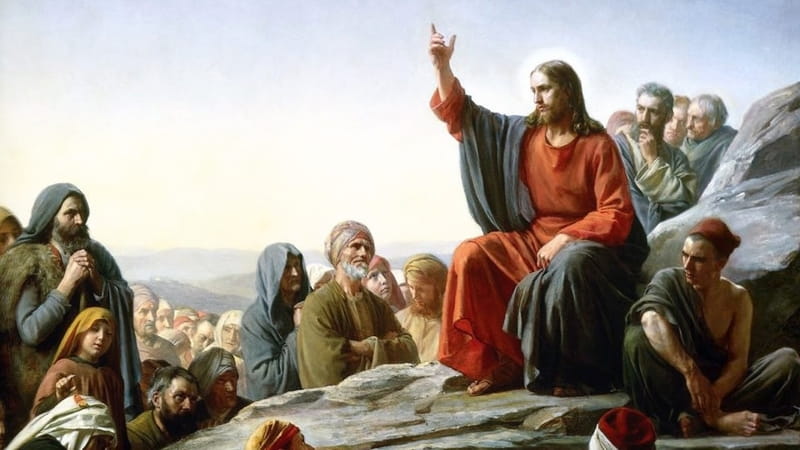

This brand of liberal theology focused on the nature of Christ as a human being. Christ is not viewed as God but as an ethical teacher and example of how to live ethically. Rauschenbusch’s Christology was decisively shaped by the quest for the historical Jesus.[3] The quest for the historical Jesus led to a focus on his ethical teaching.[4] Social Gospel proponents leaned on the Sermon on the Mount to promote a reform agenda that attacked corruption, materialism, and inequality to give preference to the poor.[5] The ethical principles of Jesus were taught as the only alternative for the greedy ethics of capitalism.[6]

Liberal theology also brought a relationship between religion and the natural sciences. The Social Gospel represented the unique American reaction to a social revolution that appeared simultaneously with the development of the physical sciences, evolution, sociology, and biblical criticism.[7] Gladden explained how a person could accept the teachings of modern science and the theory of evolution and emerge with faith intact.[8] The new social sciences and the Social Gospel were often united as the movement utilized new techniques such as the social survey to obtain realistic pictures of the social and religious needs of specific neighborhoods.[9]

Although not fully embraced by all within the movement, the Social Gospel was largely seen as bound to liberal theology. This had some benefits at the time but likely led to the downfall of the movement.

[1]Tandy, The Social Gospel in America, 85-91.

[2]Rauschenbusch, A Theology for the Social Gospel, 27-86.

[3]Tandy, The Social Gospel in America, 257.

[4]Hopkins, The Rise of the Social Gospel, 203.

[5]Littlefield and Opsahl, “Promulgating the Kingdom,” 292.

[6]Rauschenbusch, A Theology for the Social Gospel, 26.

[7]Hopkins, The Rise of the Social Gospel, 326.

[8]Tandy, The Social Gospel in America, 25

[9]White and Hopkins, The Social Gospel, 129-130.

Primary Doctrines of the Prosperity Gospel

The Prosperity Gospel is a movement, not a monolithic organization.[1] Prosperity theology is not one idea; rather, it consists of many ideas.[2] Yet while there is not a defined Prosperity Gospel theology, the members of this movement possess similar characteristics.[3]

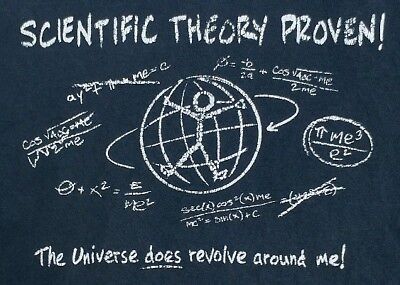

Individualism

The beginning point of the Prosperity Gospel’s teachings is the focus on the individual. It is a highly personalized faith.[4] The emphasis of the Prosperity Gospel is the individual’s relationship with God.[5] People are placed at the center of this system. Religion is to serve people and to help them get what they desire.[6] The basic premise is that God wants believers to have the best of everything.[7] The Prosperity Gospel is an egocentric gospel that teaches that God wants believers to be materially prosperous in the here and now.[8] The emphasis on the believer’s transformation heightens an anthropology centered on the individual who confesses to belong to God.[9]

Humanity is so exalted that many Prosperity preachers have promoted mankind to the highest level, claiming that humans are little gods.[10] According to Hanegraaff, in Prosperity theology, man is promoted to deity, and God is demoted to servitude.[11] Mankind can harness the power of God for personal success.[12] The believer has the right to command God.[13]

In such turbulent times as the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, this kind of individualism appealed to many who were struggling amid the masses in the cities. The Prosperity Gospel offers the opportunity for the individual to control his or her circumstances and salvation through self-discipline and belief. It gives a perception of control.[14] Individuals have no control over luck or the world’s system, but they have control over themselves. They have control over their devotion. Their devotion is what is required to succeed.[15]

[1]Hanegraaff, Christianity in Crisis, 12.

[2]Attanasi and Yong, Pentecostalism and Prosperity, 27.

[3]Hanegraaff, Christianity in Crisis, 12.

[4]Attanasi and Yong, Pentecostalism and Prosperity, 2.

[5]Wrenn, “Consecrating Capitalism,” 426.

[6]Jones and Woodbridge, Health, Wealth, and Happiness, 52

[7]Vines, SpiritWorks, 159.

[8]Jones and Woodbridge, Health, Wealth, and Happiness, 15.

[9]Attanasi and Yong, Pentecostalism and Prosperity, 101.

[10]Hanegraaff, Christianity in Crisis, 109.

[11]Ibid, 106.

[12]Jones and Woodbridge, Health, Wealth, & Happiness, 41

[13]Vines, SpiritWorks, 160.

[14]Wrenn, “Consecrating Captialism,” 428.

[15]Ibid, 430.

View of God

The rugged individualism of the Prosperity Gospel is tied to its view of God. In this system, God is not a person. Rather, Prosperity theology presents God as a metaphysical God.[1] They deny the traditional view of the Trinity and embrace the idea that God is some kind of life force.[2] God is not the Sovereign Ruler of the universe, but a puppet at the call of creation.[3] Since God is a force and not a person, there is the possibility of religious pluralism. Humans can be little gods. Other religions’ gods can be a manifestation of this life force.[4] It may be most accurate to say that Prosperity theology is henotheistic. It adheres to the worship of one overarching God while not denying the possibility of other, lower deities.[5] This allows many Prosperity preachers the freedom to draw appeal to the occult as God may work through it as well.[6]

Prosperity theology is derived from the mind-healing cult of New Thought in the late nineteenth century.[7] From this philosophy comes the idea that the presence of God is welcomed or opposed by contrasting forces of faith and fear.[8] It is the law of attraction. If an individual is filled with faith, it will attract God and the good that he brings. If the individual is full of fear, then it drives out God and welcomes evil. Phineas Quimby’s power of the mind is reimagined as the force of faith.[9] The result of this thinking is that words have a powerful force associated with them. Speaking the right words brings about a new reality.[10] The way to activate the force of faith is by proper words.[11]

These words must be associated with faithful living as well. There is usually a success formula that the individual must follow. The individual must have the faith to believe and use these success formulas.[12] Faith is the force, words are the container for the force, and formulas operate the spiritual laws of the universe.[13] This individualism and reliance on faith and formulas allow flexibility for the Prosperity preacher. The individual is praised for his or her faithfulness but is also blamed for negative confession. If the individual is not successful or healed, it is not the preacher’s fault; it is the individual’s fault. He or she simply did not have enough faith or did not have a positive confession. The preacher is off the hook.[14]

[1]Hanegraaff, Christianity in Crisis, 93.

[2]Jones and Woodbridge, Health, Wealth, & Happiness, 34-37.

[3]Hanegraaff, Christianity in Crisis, 87.

[4]Jones and Woodbridge, Health, Wealth, & Happiness, 33.

[5]Hanegraaff, Christianity in Crisis, 111.

[6]Ibid, 84.

[7]Vines, SpiritWorks, 167.

[8]Hanegraaff, Christianity in Crisis, 66.

[9]Ibid, 29.

[10]Jones and Woodbridge, Health, Wealth, & Happiness, 51.

[11]Hanegraaff, Christianity in Crisis, 66.

[12]Vines, SpiritWorks, 160.

[13]Hanegraaff, Christianity in Crisis, 94.

[14]Ibid, 78.

Cultic Faith

Hanegraaff describes Prosperity theology as cultic, though some groups he would qualify as a cult. A cult can be considered a pseudo-Christian group but can also be consider based on the sociological perspective. A cult usually involves a search for a mystical experience, lack of an organized structure, and the presence of a charismatic leader.[1] Nearly all Prosperity groups meet the definition of a cult.

Most have embraced Pentecostalism’s emotive nature. Prosperity preacher Kenneth E. Hagen combined charismatic beliefs such as speaking in tongues and miraculous gifts with the prosperity gospel, while Oral Roberts had a ministry of alleged healing.[2] Many seek to build big church buildings, revealing a desire to worship in large group settings where a fervent spiritual atmosphere assists in inducing charismatic experiences.[3]

Nearly all Prosperity groups have a preacher who has cultivated a winsome personality and a polished presentation of their message.[4] These preachers are charismatic and attractive either in physical appearance or in personality. Joel Osteen, Benny Hinn, Kenneth Hagin, and Kenneth Copeland are simply a few big names in the Prosperity Gospel, but their names are known across the United States and perhaps around the world.

The reliance upon extrabiblical revelation is also quite common among Prosperity preachers and their followers. Many claim to have experienced miraculous healing or success which is attributed to the Prosperity Gospel.[5] These signs and wonders are often used as the bait to draw people into the leaders’ circles of influence. Miracles, healings, and other supernatural phenomena are used to convince the unsaved of the reality of the gospel.[6] Several of the Prosperity preachers claim new revelations from God. They speak of dreams or visions in which God showed them the new formula that leads to success. A reliance upon extra-biblical revelation from God is a common feature of the Prosperity preacher.[7]

Capitalism

The most general teaching of the Prosperity Gospel is that if an individual is faithful to God, then God will reward that faith financially.[1] This gospel is intricately tied to capitalism. Capitalism and the Prosperity Gospel have a shared goal of achieving a state of well-being, but their departure points are divergent. Capitalism is grounded in economics while the Prosperity Gospel is based on religion.[2] The Prosperity Gospel demystifies secular capitalism by providing God as the grand orchestrator of economics.[3] The fact is that the Prosperity Gospel is fueled by utopian dreams of capitalist success.[4]

This gospel teaches that God wants the individual to have the best. Prosperity is the right of every Christian who claims it by faith.[5] The Bible is a contract to command God and Jesus is a magic mantra to control God. prosperity signifies God’s favor while poverty signifies the individual’s failure.[6] The committed must be wealthy for God does not want his children to stay poor.[7]

The Prosperity Gospel draws more from American capitalist culture than it does from the Bible. It contains a grain of biblical truth that has been distorted[8]by reading contemporary culture into the Bible. The idea of success is deeply rooted in American culture. The Prosperity Gospel rewrites the gospel into a contemporary American image.[9] It is the American Dream reshaped.[10] So much so that Prosperity Gospel churches have embraced the aesthetics of corporate America in their large, non-descript worship headquarters, equipped with stages rather than altars and a globe in the background rather than a cross.[11] Wrenn writes,

“The appeal of the Prosperity Gospel cuts across class lines: for the upper class, it further justifies their place in the hierarchy; for the middle class, it affirms their aspirations and opens the perception of possibilities; and for the poor, the Prosperity Gospel gives hope.”[12]

The Prosperity Gospel appeals to natural human desires. It promises much and requires little. Yet its teachings are not biblical. Followers of the Prosperity Gospel have little knowledge of biblical doctrine, making them ripe for distorted teachings. Many in the church possess such a lack of general discernment because they reflect the nature of the Prosperity Gospel too. They are more influenced by the secular culture than the Scriptures.[13]

There is an inherent pragmatism in the Prosperity Gospel. It is extremely adaptable. Its system can adapt to the economic demands of the current culture in whatever its context.[14] As capitalism forced the individual’s world to become increasingly focused on their careers, the gospel became more focused on finances.[15] As the focus changed to health, the gospel could adapt to focus on a person’s health. It could do the same for the family. The Prosperity Gospel says that God wants to bless believers spiritually, physically, and materially.[16]

The Prosperity Gospel is an embrace of the modern condition and an implicit acknowledgment that the world has changed.[17] It justifies the distribution of wealth according to a spiritual metric.[18] It addresses the social dislocation of people without challenging the economic sphere and ideology. Rather, it mimics it.[19]

[1]Ibid, 13.

[2]Attanasi and Yong, Pentecostalism and Prosperity, 88.

[3]Wrenn, “Consecrating Capitalism,” 430.

[4]Attanasi and Yong, Pentecostalism and Prosperity, 167.

[5]Vines, SpiritWorks, 160.

[6]Hanegraaff, Christianity in Crisis, 211-214.

[7]Attanasi and Yong, Pentecostalism and Prosperity, 153.

[8]Jones and Woodbridge, Health, Wealth, & Happiness, 18.

[9]Vines, SpiritWorks, 165.

[10]Wrenn, “Consecrating Capitalism,” 431.

[11]Ibid, 429.

[12]Ibid, 427.

[13]Jones and Woodbridge, Health, Wealth, & Happiness, 18-19.

[14]Attanasi and Yong, Pentecostalism and Prosperity, 133.

[15]Ibid, 140

[16]Ibid, 3.

[17]Ibid, 145.

[18]Wrenn, “Consecrating Capitalism,” 427.

[19]Ibid, 431.

Having covered the historical roots of the movements and the primary teachings of each movement, join me next week as I examine the major similarities and differences between the Social and Prosperity Gospels.

Leave a comment