Last week I began looking at the challenge of the prosperity gospel to missions. But where did it come from and how did it spread so rapidly?

The Prosperity Gospel is built upon a quasi-Christian heresy known as the New Thought movement. New Thought drew from the Gospels, Hinduism, philosophical idealism, transcendentalism, popular science evolution, and the optimistic spirit of progress of the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. [1] For several decades, the Pentecostal movement and the New Thought movement grew side by side. The New Thought movement merged with the Charismatic and Neo-Charismatic waves of Pentecostalism to create the Prosperity Gospel, dangerously merging biblical ideas and secular thought.[2]

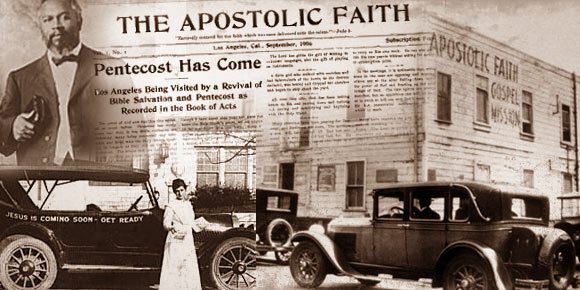

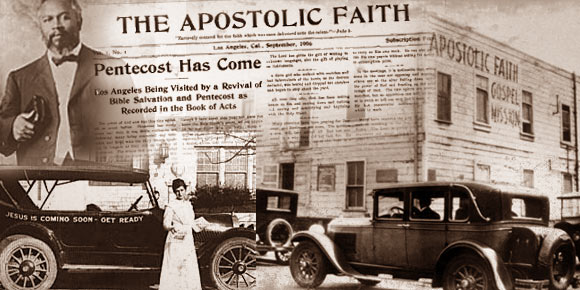

This merger brought the Prosperity Gospel the evangelistic and missiological zeal of the Pentecostal church. From its beginnings in the early twentieth century, Pentecostalism has been a multicultural movement. The Azusa Street revival in Los Angeles, California marks Pentecostalism’s conception. It attracted people of varying ethnicities and sociological backgrounds. Likewise, the merger of the Prosperity Gospel and Pentecostalism launched this dangerous teaching around the globe.

The Prosperity Gospel was birthed in capitalism in the developed United States, the world’s leading free-market economy. It developed amid the progressive globalization of modern capitalism. It is because of the effect of globalized capitalism that it has spread far and wide.[3] The general impression is that the message is an American invention.[4] The Prosperity Gospel is the American Dream reshaped and given clear instruction that through devotion toward God, patience, and belief in His blessings, prosperity will follow.[5] This is a message that appeals to many people across various cultures.

Rise of the Prosperity Gospel in Latin America

As citizens of multiple communities, Latinos have numerous religious voices competing for their attention, from social justice messages of liberationists to Roman Catholic traditionalists, and modern Evangelicals to the Prosperity Gospel. The Prosperity Gospel is one trend in the globalization of charismatic Christianity in the global South.[1] Following the collapse of the ecumenism of the charismatic-renewal movement of the 1970s, there was a vacuum in Latin America. The Prosperity Gospel stepped into the vacuum.[2]

Latinos have adopted the Prosperity Gospel despite their disproportionate poverty level because they believe that there is a correlation between faithfulness to its teachings and economic gain.[3] Under this teaching, suffering is understood as something that should be erased.[4] This is a direct contrast to traditional Roman Catholic teaching about suffering and is often embraced by the many impoverished peoples of the culture. As a result of this, numerous Prosperity Gospel churches have risen in Latin America.

[1] Patterson, Eric and Edmund Rybarczyk. The Future of Pentecostalism in the United States (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2007) 71, 77.

[2] Cleary, Edward L and Hannah W. Stewart-Gambino. Power, Politics, and Pentecostals in Latin America (Boulder: Westview Press, 1997), 83.

[3] Patterson and Rybarczyk, The Future of Pentecostalism, 77.

[4] Ibid.

Rise of the Prosperity Gospel in Asia

The rise in popularity of faith movements in Asia that articulate a strong Prosperity Gospel message is generally linked to processes of urbanization, economic development, and the rising middle class of the 1980s.[1] Sociological studies have shown a variety of generally positive impacts of the Prosperity Gospel in Asia[2], but the path has not been an easy one.

An example of the troubles of the Prosperity Gospel can be seen in Korea. Post-war Koreans generally held to a traditional fatalistic religious outlook. Then Christian missionaries came teaching about suffering and seemingly gave this fatalism a Christian veneer. Any hint of material prosperity ran the danger of reducing a highly held Christian religion into the territory of the extremely despised traditional Shamanism.[3] Then David Yonggi Cho began teaching that God cares for His people’s daily needs, including material needs. This kind of Prosperity Gospel teaching was considered a lower religion than Christianity that focused on higher issues like holiness, spirituality, and salvation. Cho was even alleged to be shamanistic as he taught about pursuing physical needs. Despite the cultural backlash, his congregation grew exponentially.[4] As Korean society has gained economic prosperity, Cho has focused more on philanthropy and missionary work.[5]

This is simply an example of what is seen worldwide. In situations where social systems provide little or no provision for daily sustenance or protection from threats to survival, religion flourishes. The Prosperity Gospel has expanded in Asia, Latin America, and Africa largely in response to a lack of social systems. The Prosperity Gospel takes these immediate concerns seriously.[6] While words and charity are not pure gifts as there is an expectation of a return of prosperity and spiritual development, these churches are willing to involve God in every aspect of human life.[7] An unnamed pastor of a church in Yogyakarta, Indonesia is quoted as saying, “We are prosperity-oriented but not just prosperity; it’s more about spiritual growth and with spiritual growth, there will be success.”[8] Therefore, the Prosperity Gospel turns religious faith into social capital. In places where Christianity is growing despite harsh circumstances, God is assumed to be involved in every part of daily life.[9]

[1] Koning, “Beyond the Prosperity Gospel,” 58

[2] Ma, Wonsuk, Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen, and J. Kwabena Asamoah-Gyadu. Pentecostal Mission and Global Christianity (Oxford: Regnum Books International, 2014), 272.

[3] Ibid, 274.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid, 281

[6] Ma, Pentecostal Mission, 289-90.

[7] Koning, “Beyond the Prosperity Gospel,” 46.

[8] Ibid, 50.

[9] Ma, Pentecostal Mission, 282, 289.

Rise of the Prosperity Gospel in Africa

The Prosperity Gospel has invaded the African continent so strongly that promotional advertisements are prevalent in many of its cities.[1] The slogans of the Prosperity Gospel are highly appealing to the masses.[2] For many of those, this gospel is part of the war against poverty.[3] As economic conditions remain difficult or worsen, promises of spiritual and material prosperity maintain a growing appeal for needy individuals and churches.[4]

The prevalence of the Prosperity Gospel in Africa is not simply caused by the perceived needs of their own people, but those from other countries as well. The Prosperity Gospel became massively popular in Africa in the 1980s. During that time, several American evangelists spread the Prosperity Gospel through crusades across the continent. Churches in Nigeria exploded after a teaching tour of these kinds of preachers, including Kenneth Hagin, Jr. and Kenneth Copeland, in the early 1990s.[5] Further, young African church leaders were sent to Prosperity conferences and schools in the United States. Benson Idahosa established a breeding camp for adherents of Prosperity teaching at his All-Nations’ Bible Seminary. The Fire Convention in Harare in 1986 demonstrated the significance of the Prosperity Gospel’s insertion in the African continent.[6]

The Prosperity Gospel’s use of media also played a significant role. As a new culture emerged in Africa that was characterized by easy access to electronic and print media, numerous seminars for African church leaders, and the new emphasis on the growth and size of ministries contributed to the publicizing of the Prosperity Gospel.[7] Additionally, many Africans gained access to television and radio. The Trinity Broadcast Network (TBN) and God TV gained large African audiences.[8] TBN serves as a platform specifically for Prosperity Gospel preachers to reach large audiences.[9] It rarely, if ever, features non-Prosperity Gospel preachers.

The Prosperity Gospel can be rich in its capacity to reimagine the gospel from an indigenous idiom.[10] This is clearly seen in the African context. For example, Yonggi Cho’s Fourth Dimension added the power of imagination, visualization, and utilizing the right word in the form of incantation to the Prosperity Gospel.[11] For Africans with a background of animism, this struck the right chord with their indigenous spirituality.[12] More about the effect of this will be examined in the next section. There can be little doubt that the Prosperity Gospel is making inroads into strategic areas of African life.[13]

Although the roots of the Prosperity Gospel are shrouded in conspiracy, its teaching has grown rapidly.[14] Its spread throughout the world has also been controversial, but its popularization has not ceased.[15] It has extended to almost every region of the globe.

[1] Hackett, Rosalind I. J., “The Gospel of Prosperity in West Africa” Religion and the Transformations of Capitalism: Comparative Approaches (London: Routledge, 1995), 199.

[2] Williams, “The Prosperity Gospel’s Effect,” 17.

[3] Hackett, “The Gospel of Prosperity,” 203.

[4] Ibid, 210.

[5] Ma, Pentecostal Mission, 279.

[6] Kalu, African Pentecostalism, 256-257.

[7] Ibid, 259

[8] Williams, “The Prosperity Gospel’s Effect,” 17.

[9] Jones and Woodbridge, Health, Wealth, & Happiness, 50.

[10] Kalu, African Pentecostalism, 262

[11] Ibid, 257.

[12] Williams, “The Prosperity Gospel’s Effect,” 13.

[13] Hackett, “The Gospel of Prosperity,” 210.

[14] Williams, “The Prosperity Gospel’s Effect,” 12

[15] Ma, Pentecostal Mission, 272.

Next week I will continue this examination to see the effects of the Prosperity Gospel in each of the areas I wrote about this week.

Leave a comment